A year ago this week the era of Apple silicon truly began, as the first reviews of M1 Macs arrived, followed shortly thereafter by M1 Macs arriving in Apple Stores and in the hands of Mac users everywhere.

We had hope that the future would be brighter with Apple-designed processors, but that optimism was tempered by Apple’s recent Mac missteps. There were also a lot of questions about a processor that had only really seen success in iPhones and iPads. Would there be unexpected pitfalls of abandoning Intel? Could Apple pull off its latest Mac chip transition with the same skill that it showed during the two previous transitions?

Twelve months later, the answers are much clear: We’re in the brightest timeline.

The Mac is in a safer place

Right away it was clear that the M1 would provide to the Mac what we had all hoped it would: impressive performance and excellent power efficiency–leading to great battery life on laptops. Over the last year, as Apple-designed chips have spread to most Mac models, those facts have remained intact.

In just the last month, one of the biggest questions of the entire chip transition has been answered. The M1 chip was capable enough to run lower-end systems that needed about as much processing power as an iPad Pro, but could Apple’s chips scale to meet the needs of professional Mac users? With the release of the MacBook Pro with M1 Pro and M1 Max chips, we got the answer. It’s a definitive yes.Apple’s

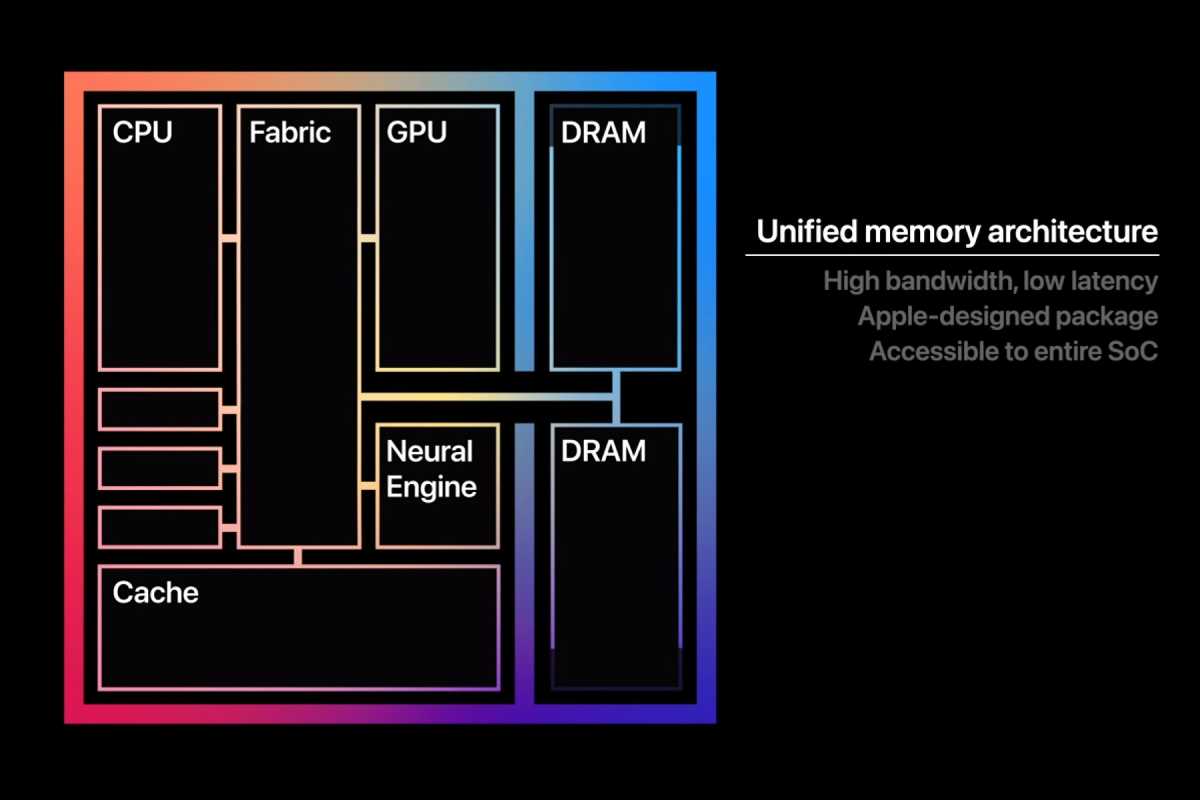

This was not a given. It’s easy to say “just throw more processor and graphics cores at the problem,” but computer performance doesn’t necessarily scale so easily. Apple’s advantage really came into play with its unified memory architecture, which doesn’t just offer a lot of fast memory for processing operations, but also offers an enormous pool of fast memory for GPU use.

A few years ago, if you had told me that Mac laptops would be shipping with 10-core processors with 32-core GPUs, I would believe you–but I would have been seriously impressed that Intel had managed to make those processors and that Apple had been able to ship them in its laptops.

Bottom line: Apple’s skill in making chips for iPads and iPhones does translate to the Mac, after all.

Apple

There were very few growing pains

Shifting to an entirely new processor architecture isn’t easy, but Apple has done it to the Mac three times, and in every case it’s acquitted itself well. That said, there’s probably nobody left at Apple who worked on the PowerPC transition, and even the Intel transition is probably only a distant memory in the mind of the most grizzled of veteran Apple engineers.

And yet the streak remains intact. In fact, I’m tempted to call the past year painless. Compatibility has largely been a non-issue, starting with Rosetta 2, the code-translation system that allows Intel-based apps to run on Apple silicon without trouble. Rosetta got a huge leg up with the speed of the M1 chips, of course–it’s a lot easier to run translated code when it’s running on a really fast processor–but Apple also did a good job in letting translated apps tie into native code that runs at full speed. (For example, an Intel-built game using the Apple silicon-native Metal graphics engine may run faster on an M1 Mac than it did on an Intel model.)

As someone who relies on a few apps that were what Steve Jobs used to call “laggards”–they took a long time to run natively on Apple silicon, or are still not there–I am happy to report that they run just fine, to the point where it doesn’t matter that they’re not native. (And yet, I am angry at those laggard developers, because I know their software could run much faster than it does. One of these days they’ll release an update and all of a sudden, those apps will fly. I continue to wait.)

Even better, it seems like there are very few apps that are actually laggards. Most of my apps embraced Apple silicon very, very quickly. That’s down to the flexibility and motivation of Apple’s developer community, and to Apple for providing them with tools to make the transition relatively painless.

The competition doesn’t have an answer

Apple’s long-time frenemy Qualcomm insists that it is going to make chips that can match up with Apple silicon–maybe by 2023. Fans of PCs running AMD and Intel processors cling to the fact that while the new MacBook Pros might be the fastest laptops around–especially if you unplug them from the wall–at least there are still more powerful computers on the desktop. (Let’s see what happens when Apple releases its Apple silicon-based Mac Pro.)

The truth is, Apple caught the tech world flat-footed. They’re all scrambling to catch up. Apple was already more than a year ahead of Qualcomm, every single year, in terms of smartphone processor performance. Now it’s shown that it can extend that performance to the Mac–and in the process, use all the tricks it used to surpass Qualcomm to blow past Intel, too.

But rest assured, they all know now. Qualcomm’s next-generation processor (which might challenge the M series in a couple of years) will be designed by a company founded by Apple silicon engineers which was recently bought by Qualcomm. Intel talks about having to beat Apple at its own game–or, failing that, convince Apple to use Intel’s factories to build Apple-designed chips.

The game continues. The future isn’t guaranteed. But Apple has the drop on the competition, and this past year has shown that everything we thought Apple’s chips might be able to do, they can do.

The system on s chip that Apple puts in the Mac Pro will be an important indicator of the capabilities of Apple silicon.

Apple

The transition’s half over

As with the transition from PowerPC to Intel, Apple’s first steps from Intel to Apple silicon were conservative. The MacBook Air, Mac mini, and 13-inch MacBook Pro were identical on the outside–but transformed on the inside.

Then came the next step, with new designs (the iMac and MacBook Pro) being coupled with upgrades to M-series processors. A redesign of the MacBook Air is likely on the horizon.

Now that the professional-level version of the M1 chip has arrived, there really aren’t that many chapters left to write in the story of the transition to Apple silicon. All along, Apple has said that this is a two-year transition, and it sure feels like it will meet that self-imposed timetable.

All that is left to revise is the Mac Pro, the larger iMac, and the high-end Mac mini. All but the Mac Pro could probably be solved with the existing M1 Max and M1 Pro chips. And with a second generation of M-series processors due in 2022, who wants to bet against Apple shipping an M2 Max Mac Pro about 12 months from now?

Not me. If the last year has taught any of us anything, it’s that Apple silicon delivers. I don’t expect the next year to change that perception one bit.

from Macworld.com https://ift.tt/3ciVubs

via IFTTT